Rebecca is a 5-year-old primary 2 pupil of Muwonleru Grammer School, Ibadan. She is a very smart and lively child and this has made her the most preferred amongst her siblings and even at school. Her father is a mechanic and her mother, a petty trader at the village square. The family of 6 resides in an uncompleted building with some interesting occupants (poultry, bird dung, rusty blades and nails all over the floor), nice neighbors (huge refuse dump) and a host of other mind-burgling eyesores. She was in a relatively normal state of health until she came down with muscle spasms and inability to close her mouth, having sustained an injury while playing around the house with her other siblings, as her mother narrated to the physician. She has not been immunized at all either her mother, take the required doses of tetanus toxoid during pregnancy. After weeks of self-medication with honey and some other antibiotics, Rebecca was admitted to the hospital where a diagnosis of Generalized Tetanus was made. Thankfully she survived after she was given Tetanus toxoid (TT) and Anti-Tetanus Serum (ATS). But the family sank into deeper financial crises after a series of tests and treatments.

After 15 years of childlessness, Mrs. Kubayanka was delivered of a bouncing baby boy. Imagine the joy and anxiety when she approached her 9th month of gestation; her mother-in-law, even suggested they have the baby in their village’s Mission Home because she trusted the midwife there. Moreover, the midwife had helped deliver the majority of the children in that community. But the birth experience was quite eventful. At the onset of labor, she was rushed to the mission home and was immediately put to sleep with some unknown drugs. The midwife took a pair of scissors which had been lying on the floor for decades and cut her underneath on account of obstructed labor, afterward one of the apprentices retrieved a half-broken razor blade and ‘slit the cord’ of the child. As Mrs. Kubayanka woke up to the news of her baby boy’s arrival, she gave him a very warm embrace despite the excruciating pain and discomfort from all the invasive procedures. They were later discharged home that day and life took a U-turn for the new family of 3. Some days later, little Tobey came down with fever and chills, he refused every food that was given and began to convulse. His mother had earlier come down with similar symptoms but ignored them ‘for the love of her only child’. Meanwhile, the drugstore had run out of most vaccines (I recall that the mother did not even attend antenatal care during the pregnancy). As symptoms progressed, both parties grew worse and we have just returned from their burial ceremony as I speak.

The menace that Tetanus poses to the society is fast becoming a fatal nuisance and all hands should be on deck to prevent this monstrous evil from causing more harm than it has done already. On this note, we shall, therefore, delve into the world of information on Tetanus.

WHAT IS TETANUS?

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a potentially fatal bacterial infection caused by the toxins (spores) of the organism, Clostridium tetani. These toxins are found everywhere in the environment; particularly in the soil, ash, intestines or feces of animals and humans, surfaces of the skin and that of rusty nails, needles, barbed wire. Being heat and antiseptic-resistant, the spores can survive for years.

Tetanus within 6 weeks of the end of pregnancy is ‘maternal tetanus’ and within the first 28 days of life is called ‘neonatal tetanus’ as we have seen in the case of Mrs. Kubayanka and little Tobey.

HOW MANY HAS TETANUS AFFECTED?

Tetanus is not relative to age, sex, race or socioeconomic status although it remains a public health concern in many low-income countries (due to unclean birth practices and low immunization coverage). It is also most serious in newborns and pregnant women who have not been sufficiently immunized with tetanus-toxoid-containing vaccines.

In 2017, tetanus killed about 30,848 newborns, a 96% reduction from the situation in 1988 when an estimated 787,000 newborn babies died of tetanus within their first month of life. Sadly, Nigeria is one of the 27 countries which account for over 90% of the global burden of neonatal tetanus.

HOW TO RECOGNIZE TETANUS?

The symptoms of tetanus appear anytime from a few days to several weeks after the infectious agent enters the body through an infected wound. The period between when infection and manifestation of signs and symptoms is averagely 3– 21 days. The common signs and symptoms include:

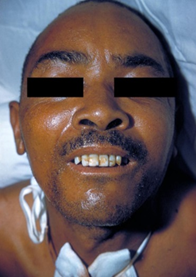

- Spasms and stiffness of the jaw muscles (lockjaw/trismus)

- Stiffness of the abdominal muscles, facial muscles (risus sardonicus)

- Difficulty swallowing from spasms of neck muscles

- Difficulty breathing due to stiffness of chest muscles

- Headache

- Urinary symptoms like pain, retention, and loss of stool control

Other signs which may be noticed by the physician include:

- Fever

- Opisthotonus (arching of the back from spasms of the back muscles)

- Excessive sweating

- Elevated blood pressure

- Rapid heart rate

WHO MAKES ONE PRONE TO TETANUS?

There are some factors that increase a person’s chance of getting tetanus. They include:

- Failure to get vaccinated or to keep up to date with booster shots against tetanus

- A foreign body such as a nail or other sharps

- An injury that allows the disease agent to enter the wound

Tetanus cases have developed from these instances as well: puncture wound, burns, fractures, surgical wounds, injection drug use, infected foot ulcers (e.g., in diabetics), dental infections, infected umbilical stumps in newborns of inadequately vaccinated mothers, etc.

UNTREATED TETANUS CAN LEAD TO:

- Fractures due to persistent spasms

- Blockage of a lung artery leading to suffocation

- And eventually, death

PREVENTION IS BETTER

Tetanus can easily be prevented through immunization with tetanus-toxoid-containing vaccines (TTCV), which are included in the routine immunization programs (for children) and during antenatal visits (for pregnant women). WHO recommends 6 doses; 3 primary plus 3 booster doses of TTCV.

The 3 primary doses should begin as early as 6 weeks of age with subsequent doses given at a minimum interval of 4 weeks between doses. The 3 booster doses should preferably be given during the 2nd year of life (12-23months), at 4-7years and at 9-15 years of age respectively. Ideally, there should be at least 4 years between booster doses. The DTaP (Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) vaccines can be used alongside others. Neonatal tetanus can be prevented by immunizing women of reproductive age with TTCV, either during pregnancy or outside of pregnancy.

WHEN TO SEE A DOCTOR

See your doctor for a tetanus booster shot if you have not had a booster shot within 10 years, or you have a deep or dirty wound and you have not had a booster shot in 5 years. If you are not sure of when you received your last booster, get a booster.