By Samuel Omofala

About seventeen and a half centuries ago, the killing of a man (some accounts say two men) by the Roman Empire laid the foundation for a global feast accepted as one of the most important public holidays throughout the world. Today, almost every part of the world celebrates love in a grand style and attractive colours.

From Martyrdom to Canonisation to Legends

Roman Emperor Claudius II was said to have executed two men named Valentine at different times during his short two-year reign between 268 and 270 AD. Scarce information makes it impossible to be certain whether the two supposed martyrs were one and the same, but the two accounts state that one of them was a bishop who conducted marriages for soldiers contrary to imperial orders and was beheaded by a prefect, while the other states that the martyr was a priest killed by the order of the emperor himself.

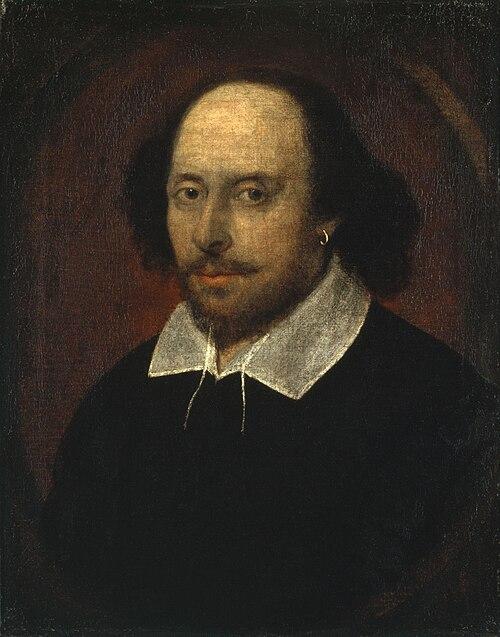

Upon the declaration of Pope Gelasius, the Catholic Church set aside February 14 to commemorate the martyrdom around 498 AD, and this soon became universal as the gospel spread. Poet and playwright Shakespeare made an allusion to the day in his popular play Hamlet, where in Act IV, Scene V, Ophelia sings a ballad:

“To-morrow is Saint Valentine’s day, / All in the morning betime, / And I a maid at your window, / To be your Valentine.”

Shakespeare, again in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, referenced Valentine as the ideal lovemate one would give the world when the fairy king Oberon vows Titania a magical experience, calling her “a valentine as never was seen.” Valentine is also a character in Shakespeare’s The Two Gentlemen of Verona.

There is no denying that Shakespeare is one of the greatest literary icons in history and his plays have a far-reaching cultural impact, thanks to the transcontinental reach of the English language and literature. Hamlet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream are also two of his most popular plays, with performances and adaptations staged in various parts of the world.

Other literary figures that propagated Valentine in their works include Geoffrey Chaucer, referred to as the father of English literature in his 14th century poem Parliament of Fowls and John Donne in On the Lady Elizabeth, and Count Palatine Being Married on St. Valentine’s Day, a poem commissioned to celebrate the royal marriage of the then English Princess with Fredrick V, an elector of the Holy Roman Empire, on February 14, 1613.

The Industrial Revolution came with an economic boom that allowed even peasants access to some basic items and experiences which used to be luxuries. Romance was one of these experiences and thus, Valentine’s Day moved away from being a church feast and an upper-class celebration to pop culture. All of these have shaped the understanding of February 14, originally a feast in memory of a saint, into a celebration of lovers.

The Nigerian Valentine: Ego and Social Validation

The Nigerian Valentine is neither a socio-religious celebration as practised by the Catholics, nor a romantic adventure as in the Shakespearean world.

The Nigerian Valentine is a day of show-off, a “I better pass my neighbour” contest, in which women’s status is measured by how expensive the gifts given to them by their men are. God forbid a woman has no man on this day.

Who is to be blamed? Clearly, it is not as it seems. Here, “na we dey take care of women” is not just a slang, it is a philosophy which men adopt as a metric of success and a key performance indicator of comfortable living. “Broke men don’t deserve love” was not coined by a gender; it was generally accepted. Men are told to hustle until they can afford to take care of their women.

This is also contrary to how the lower class celebrated Valentine’s with the exchange of letters, cards and roses during the Industrial Revolution. The Nigerian Valentine uses gift trays and money bouquets that cost as much as the minimum wage as symbols of love, not regarding the country’s status as a poor, developing nation.

The situation is no better among young adults. The day is also a day of showcasing materialistic romance, even among Nigerian students. Simplicity, one would have thought, would be sufficient for lovers who are just trying to find their feet in life, but campuses are not immune to the reality of Nigeria’s money-centred dating culture. For many young adults, campus is not just a place; it is a transitory phase between dependency and independence, a place in which life—career and love—are expected to be figured out. Magixx and Ayra Starr’s Love Don’t Cost A Dime seems to be just for the playlist among its main audience, young adults. A perfect romance among young adults definitely should not be judged on how February 14 is celebrated alone. Young adults should not be pressured into relationships just to appear perfect for a day.

Another thing about the Nigerian Valentine is that it is usually one way; from the male lover to the female lover with little to no expectation of any consideration in return. The reasons are not far-fetched from what has been stated: this arrangement boosts the Nigerian male’s ego and validates the female’s social stratum. This is nothing but the death of romance and a rise in show-off.

Perhaps the tragedy of the Nigerian Valentine is not that we celebrate love differently, but that we have reduced love to what can be bought and displayed. When a day meant to honour sacrifice becomes a competition of egos, when young adults stretch empty pockets to prove full hearts, something vital is lost. Until we learn to separate love from loot, Valentine’s Day in Nigeria will remain what it has become: not a celebration of the heart, but a parade of the wallet. Contrary to some criticism of the day, what we do in Nigeria is Valentine’s Day, but the Nigerian Valentine’s Day.